Our Lost History

(A post from my friend Matthew’s blog. I haven’t read this book.)

I recently read The Lost History of Christianity – The Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa and Asia- and How It Died by Philip Jenkins (2008). It is a magisterial introduction to a rich but largely forgotten history. The lands Jenkins has in mind were well and truly the centre of the Christian world for well over a thousand years, even after the Muslim invasion of these lands from the seventh century.

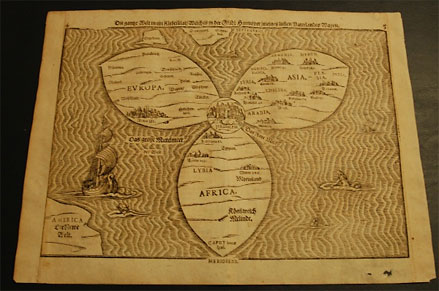

To understand the Middle East, Africa and Asia as the centre of Christian gravity at any time might now seem as natural today as arguing that the Buddhist homeland was once Buddhist. But Jenkins argues that even in 1200 AD there were 21 million Christians in Asia and the proportion of the world’s Christians living in Asia and Africa was 34 per cent. These Christians are different from us, but they had a rich and vibrant church life of academia (far above anything the Western Church approached until at least the 14th century), liturgy (which may be the source of Gregorian Chants) and mission (particularly the Syrians, who quite successfully reached into India, central Asia and China).

Before England had an archbishop of Canterbury – possibly even before Canterbury had a church – the Syrian church had established metropolitan sees in Merv and Herat, modern Turkmenistan and Afghanistan. Before Poland was Catholic, before Good King Wenceslas ruled a Christian Bohemia, the church in Bukhara, Samarkand and Patna had all reached metropolitan status. Our mental maps of Christianity are too small, and we can’t understand Christian history without Asia – or Asian history without Christianity.

Which makes the decline of these churches all the more tragic. The number of Christians in Asia in 1500 had fallen from 21 million to just 3.4 million. Most of these great churches ceased to exist, whilst the ones that did were small, marginalised and associated ethnic minorities. Churches who’s leaders had once commanded the respect and obedience of at least a quarter of the world’s Christians (and had prayed for the gospel of Yeshua to transform lives in Tibet and Java) was reduced to scratching out an existence in the hills.

Jenkins tells the stories of the churches and what happened to their survivors in the 20th Century. He also offers advice on what to do when churches die, particularly such large slabs of area where almost all Christian history has been totally eradicated. I recommend this book to anyone who is interested in Church history, particularly for those interested in the meaning of that history for today.