A Man Who Sues God

or Correspondence Will Be Entered Into

The recent Australian federal election resulted in a hung parliament, with the balance of power held by a small number of elected independents. Not being forced to toe the party line, each of these men is free to stand for the needs of his own electorate. This can certainly slow down the process of government in the courts of men, but not in the courts of God.

As Christians, we are taught to toe the party line. This is a false piety. Our Father actually loves a lively, argumentative parliament. The process of maturity is supposed to bring us to the point where we are wise judges whom He can include in His government (pictured in baptism), standing on the crystal sea as joint heirs with His Son, Great Prophets whose very words change history.

Back room deals and bargaining with God are an abuse of prayer. Or are they? Not when those disputing with God are men whose hearts are like those of the Father. Abraham and David did it. God’s desire is that we should be like them.

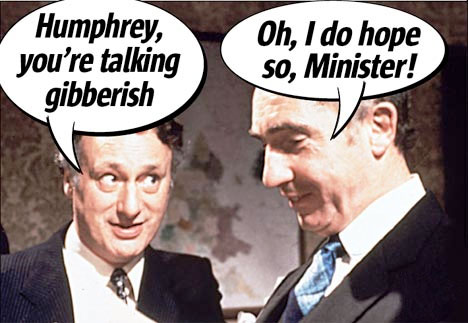

As Covenant heads, Christ, the ministers, the husbands and the fathers to whom He has given authority, have the same responsibility as the ascended Son of God: advocacy. Sadly, our lack of perseverance in prayer becomes an unspoken fatalism. As is the way with our appointed political advocates, the church culture’s party line is to pray like Sir Humphrey Appleby in Yes, Minister. Doug Wilson says,

There is a great difference between complaining about God and complaining to God. Arguing with God, complaining to God, is not inconsistent with piety. We must let the Bible teach us how to relate to God.

When the children of Israel are in the wilderness complaining about the food; when you’re driving around downtown in the rain and the windshield is fogged up and the kids are irritating you from the back seat, and you are muttering under your breath, you are not bringing your concerns to God.

We all understand that such murmuring is sinful. We don’t want to be like the Israelites whose bodies were scattered in the wilderness because they displeased God. But if we turn to the Psalms, we find that David and the other psalmists bring their complaints, concerns and agonies to God. They let God know all about it.

If you try to avoid murmuring about God by not saying anything at all, you are actually trying to be holier than the Bible, holier than the men whom God has set before us as a godly example.

We should all know what happens to those who murmur, complain, moan and grumble. Their bodies are scattered over the desert. But the alternative to this is not stiff-upper-lip stoicism.

In Psalm 55:2, David makes a noise so that God will hear him. If you want to pray like God’s saints in the Bible, lay out your case before Him. Reason it through. Don’t pray like you were a block of wood or you will get answers of the sort that would satisfy a block of wood: tepid, anaemic responses.

The Psalms teach us to sing and pray and argue rightly. The faithful servant in prayer does not want to simply “say the right words.” He wants an audience. He wants God to hear, and prays as though he wants God to hear. He wants to offer up prayers that cannot be refused. You come like the widow who wanted justice from the unjust judge: she wouldn’t leave him alone. Jesus said, “Be like that!”

But we, thinking that it reveals a high doctrine of the sovereignty of God, fall into, not Calvininsm, but stoicism. “Whatever was determined from the foundation of the world is going to happen and I can’t stop it.”

But that is a distortion of the sovereignty of God. He does not teach us to pray, “I am the sovereign God. Just sit there like a block of wood and take it.” That is not what we are called to do.

The great Puritan Goodwin said that when we pray to God we should “sue him” for things. A Puritan said that? Yes, they were Biblical people.

Now, we shouldn’t sue God in the court of the devil, or in the court of the world. But we should go into the courts of heaven and plead our case with God. You might say, “I’m not competent to plead a case of any complexity.” Well, John Bunyan said it’s better that your heart be without words than your words be without heart. It’s not prim and proper words that count. It’s heart.

This is the first thing we learn from Psalm 55. David is in trouble, and he itemises his troubles to God. He wants to tell God all about it and he wants God to do something about it. He pleads his case with Him. “Lord, hear me. Give ear to my prayer, O God, and hide not thy face from me.” Where are you going, God? Don’t hide! Hear me out, here. Attend to me, I tell you!

Now, does that sound godly to you? No it doesn’t, and the reason is that we have our own tradition of what a pious prayer sounds like:

“Dear Father in heaven, Whatever happens, happens. And bless everybody indiscriminately in such a way as I can’t tell whether or not anything has ever happened.”

We’re afraid of getting a “no,” so we build escape hatches into all our prayers. If you get a “no,” you are getting some feedback and you are learning how to pray. What you want to do is submit yourself to the text of Scripture, pray the way God’s people prayed, and as you do so you will discover that you are imitating it rightly in some instances and wrongly in others, and you make adjustments.

Remember the acronym, G.A.S.P. God Answers Specific Prayer. If that doesn’t sound pious, then we have something wrong with our definition of piety. And I submit that we have allowed ourselves to drift into these misunderstandings of piety because we have not been singing the Psalms. We are not steeped in the Psalms. If kids in the Christian church were steeped in the Psalms, marinating in them for ten or fifteen or twenty years as they grew up in the Covenant community, these false traditions of piety could not take root. You could not get away with telling people, “This is how you pray. Don’t say anything specific.”

There are actually seminars for aspiring politicians which teach them how to answer questions without saying anything. When someone on television talks for three or four minutes and nothing clear ever comes out, that’s not natural. One has to study to do that, and they do study. And we have our own schools which teach Christians how to pray that way.

Argue like David did. Argue like the apostle Paul did. Don’t complain about God. Bring your case to God. [1]

For me, one of the most striking examples of such prayer comes from the life of John G. Paton. What made it so memorable for me was the common, uncomplicated and very achievable ministry of advocacy it portrays, and the results that simple, persistent dealing with God can have as a foundation for the courageous faith of those for whom we advocate, and for the sovereign God in changing the history of His world. John Piper writes:

John G. Paton was a missionary to the New Hebrides, today called Vanuatu, in the South Seas. He was born in Scotland in 1824. I gave my Pastors’ Conference message about him because of the courage he showed throughout his 82 years of life. When I dug for the reasons he was so courageous, one reason I found was the deep love he had for his father.

The tribute Paton pays to his godly father is, by itself, worth the price of his Autobiography, which is still in print. Maybe it’s because I have four sons (and Talitha), but I wept as I read this section. It filled me with such longing to be a father like this.

There was a “closet” where his father would go for prayer as a rule after each meal. The eleven children knew it and they reverenced the spot and learned something profound about God. The impact on John Paton was immense.

Though everything else in religion were by some unthinkable catastrophe to be swept out of memory, were blotted from my understanding, my soul would wander back to those early scenes, and shut itself up once again in that Sanctuary Closet, and, hearing still the echoes of those cries to God, would hurl back all doubt with the victorious appeal, “He walked with God, why may not I?” (Autobiography, p. 8 )

How much my father’s prayers at this time impressed me I can never explain, nor could any stranger understand. When, on his knees and all of us kneeling around him in Family Worship, he poured out his whole soul with tears for the conversion of the Heathen world to the service of Jesus, and for every personal and domestic need, we all felt as if in the presence of the living Savior, and learned to know and love him as our Divine friend.” (Autobiography, p. 21)

One scene best captures the depth of love between John and his father, and the power of the impact on John’s life of uncompromising courage and purity. The time came for the young Paton to leave home and go to Glasgow to attend divinity school and become a city missionary in his early twenties. From his hometown of Torthorwald to the train station at Kilmarnock was a 40-mile walk. Forty years later, Paton wrote,

My dear father walked with me the first six miles of the way. His counsels and tears and heavenly conversation on that parting journey are fresh in my heart as if it had been but yesterday; and tears are on my cheeks as freely now as then, whenever memory steals me away to the scene. For the last half mile or so we walked on together in almost unbroken silence – my father, as was often his custom, carrying hat in hand, while his long flowing yellow hair (then yellow, but in later years white as snow) streamed like a girl’s down his shoulders. His lips kept moving in silent prayers for me; and his tears fell fast when our eyes met each other in looks for which all speech was vain! We halted on reaching the appointed parting place; he grasped my hand firmly for a minute in silence, and then solemnly and affectionately said: “God bless you, my son! Your father’s God prosper you, and keep you from all evil!”

Unable to say more, his lips kept moving in silent prayer; in tears we embraced, and parted. I ran off as fast as I could; and, when about to turn a corner in the road where he would lose sight of me, I looked back and saw him still standing with head uncovered where I had left him – gazing after me. Waving my hat in adieu, I rounded the corner and out of sight in instant. But my heart was too full and sore to carry me further, so I darted into the side of the road and wept for time. Then, rising up cautiously, I climbed the dike to see if he yet stood where I had left him; and just at that moment I caught a glimpse of him climbing the dike and looking out for me! He did not see me, and after he gazed eagerly in my direction for a while he got down, set his face toward home, and began to return – his head still uncovered, and his heart, I felt sure, still rising in prayers for me. I watched through blinding tears, till his form faded from my gaze; and then, hastening on my way, vowed deeply and oft, by the help of God, to live and act so as never to grieve or dishonor such a father and mother as he had given me. (pp. 25-26)

The impact of his father’s faith and prayer and love and discipline was immeasurable. O fathers, read and be filled with longing. [2]

Quite a few people have asked me for a more clear definition of what Ascension means in the Bible Matrix. This is it. A Covenant head who is bread and wine: the ceaseless, specific advocacy of an upright man in the throneroom of God for those whom God has given him as a body. After twenty-six years of being a Christian, I feel like I am only just beginning in prayer.

__________________________________________________

[1] Doug Wilson, Psalm 55: Mischief in the Midst of It. Christkirk sermon podcast, 12 October, 2010.

[2] John Piper, John G. Paton’s Father.

October 20th, 2010 at 3:22 am

wow….just….wow!