The Eye of Sound

Holistic Impression

On the shape of biblical language, John Breck writes:

How are we to read the Bible?

The question invites a reply that expresses an attitude: we should read it with respect, with devotion, with curiosity, perhaps even with awe. Certainly these are appropriate responses. Our concern in this present study, however, is not with attitudes but with the approach we use.

Should we read Scripture the same way we read a newspaper? Or a novel? Or a poem? Or is there some other approach by which we can sound the depths of the biblical message, to perceive what the Church’s spiritual elders called its “theandric” quality, its inner nature as a work of both human intention and divine inspiration?

To answer this question, we will concentrate on another which is still more basic: what is the “shape” of biblical language? Given the fact that the meaning of a literary text is expressed by semantic and syntactic relationships — that is, by the “form” of the passage — we want to ask about the specific principles of composition that biblical writers drew upon in order to convey their message. That inquiry defines the purpose of this book. For once we understand those principles, then we will be able to read the Scriptures appropriately. We will read them as they were intended to be read (and heard) by the biblical authors themselves, rather than through the lens of our own arbitrary presuppositions.

The author of a novel usually adopts the traditional narrative or story form of expression: providing a setting, introducing characters, developing the plot, working toward a climax, and ending with a conclusion that draws the elements of the story together into a coherent whole. The movement of narrative or story telling is basically horizontal or chronological, proceeding in a line from past to future. “Flashbacks” may add interest and detail to the story, but they still conform to the thematic development from beginning to end, from first word to last. We are so accustomed to this pattern that any deviation from it tends to confuse us. Poetry, both metric and free, is the despair of many people today, primarily because they have never acquired a sense for reading a poem as something other than narrative. Yet a good poem expresses meaning not so much through linear development of theme as through what we might call “holistic impression.” It speaks in thought-images that focus from a variety of perspectives upon the specific aspect of reality and experience the poet seeks to evoke. Every phrase, every line, every strophe is structured so as to impress a particular comprehensive truth upon the mind and the heart of the reader. In addition, poetry possesses a “self-referential” quality which enables each word or phrase to illumine every other. However much it may “tell a story,” its basic movement is concentric rather than linear, flowing from and about, as well as toward, its central theme. Like the petals of a flower, the language of a poem unfolds from, yet leads the eye back to, its vital core.

Prose and poetry can express their message in a variety of ways. While any meaningful passage conforms to some degree to the laws of narrative, the ultimate sense of an author’s work is not necessarily expressed by its conclusion. A “whodunit,” of course, must adhere to the linear principle of narrative flow, in order to preserve suspense until the end. Other more noble forms of literature, on the other hand, often convey their meaning as a poem does, by repeatedly reflecting the author’s primary theme with a variety of images and nuances. As we shall discover, it is also true of much of the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures, whether they were composed as poetic pieces (psalms, hymns, prophetic oracles) or as narratives (most of the Pentateuch, Gospels, and Epistles).

Excerpt from “New Directions in Biblical Criticism,” chapter one of John Breck, The Shape of Biblical Language, Chiasmus in the Scriptures and Beyond. Available from www.biblicalhorizons.com

Bible Mind Map

“A mind map is a diagram used to visually outline information. A mind map is often created around a single word or text, placed in the center, to which associated ideas, words and concepts are added. Major categories radiate from a central node, and lesser categories are sub-branches of larger branches. Categories can represent words, ideas, tasks, or other items related to a central key word or idea.” (Wikipedia)

The Bible is constructed organically. (See Tree and Forest.) Its complete shape was in the mind of God when the first word was spoken as a seed. As one traces the trunk, branches and twigs (or arteries, veins and capillaries) one develops a mental map of the entire body of Scripture. I believe the identification of these structures solves many theological debates. Intelligent people throw proof texts at one another without any regard to literary structure. But literary structure is what identifies the context of those very texts.

Since I can remember, I have always “seen” music as I listened to it. Apparently, this is called synaesthesia. Different sounds have different shapes and colours. As I’ve studied the Bible, without doing it deliberately I have developed a “mind map” that helps me find my way around. I can see how one “fractal” shape fits within another, which is why I often state weird things on here and expect everybody to see them as obviously as I do. It’s why I follow Augustine’s breakdown of the Ten Commandments rather than the one we are familiar with. I’ve had to modify a few things, but only in minor ways. I tried to describe its “shape and sound” for somebody recently. It was a lot of fun:

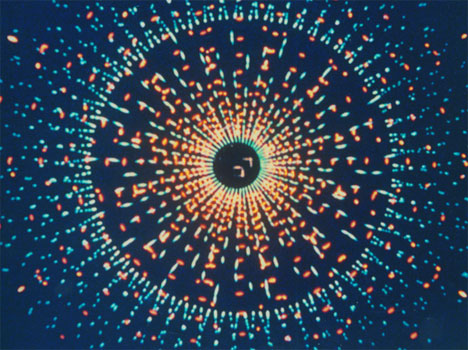

Every part of the Bible has an external shape and an internal movement. I see it in 3D. It resembles a whole lot of ziggurats, or cogwheels, or millwheels, or floating staircases, of different sizes inside a big one, and they all fit together like they are alive and grew that way, and they are all slowly rotating, each one carrying you through its cycle to the next, cycles within cycles — like a musical scale being played at different speeds and in different registers all at once. And each step in each cycle is a different material and has a different character, smell and musical pitch, but they are always in the same order. And all the events and types attached to each step (Creation day, Feast, natural material — gold, wood, bronze, blood, ivory, silver, perfume, water, light — movement up or down or through or over or under or into or out-of, opening and closing, silences, sounds and people) are struggling to describe that step, and growing out of it. But they all relate, and they are all the outworking of the shape of the Trinity and the mission of the Son for the Bride. And revolving together they sound like all music ever, playing at once but in perfect harmony. I can’t hear the music, I can only see it, but it’s deafening. Escher would have died trying to draw it. From a distance it’s a roughly globe-shaped cloud of metallic stars, or fiery knives or military shields, a nebula of carefully networked images arranged in waves, and the possible thought-connections between its parts are overwhelming, infinite. And though they are all the same shape, each piece reflects every other piece in a unique way. And it’s moving. It’s a vehicle. But when I’m reading the Bible, I know whereabouts I am inside it because it’s more fleshy, natural, and flattened out, linear, with the step patterns as a sort of 3D holographic map. But it’s still a map of visual progressions. If I discover a new connection when comparing similar structures I feel like Someone’s been there before and deliberately arranged it.

ART: Still from Allures (1961), 16mm film by Jordan Belson. Read about it here.