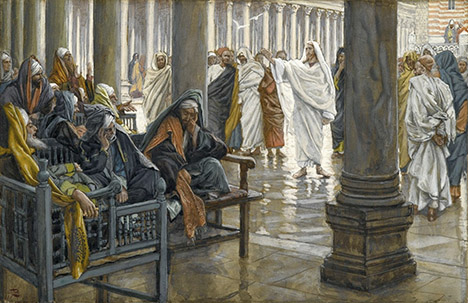

Squinty-eyed Pharisees

“…who were the Pharisees in their real setting? Where did they come from? There are no such people in the Old Testament, but when we get to Matthew they seem to be hiding behind every rock and shrub.”

Essay by Daniel Hoffman

If people today know anything about the Pharisees, they know them as the villains of the New Testament. Those who know a little more probably have a conception of the Pharisees as overly strict, eating their gruel with a scowl and casting condemnation in every direction, while Jesus was open and chill. Some might go beyond this and imagine the Pharisees as the perfect (or perfectly bad) model of self-salvation: The Pharisees wanted to save themselves by their good works, but the New Testament (it’s thought) is all about salvation through faith, and works are no big deal.

But who were the Pharisees in their real setting? Where did they come from? There are no such people in the Old Testament, but when we get to Matthew they seem to be hiding behind every rock and shrub. What was their reason for being? What was their agenda? If they were so awful, why does Jesus seem perfectly friendly toward Nicodemus? Why were there Pharisees in the Christian assembly (Acts 15:5)? Why did Paul still consider himself a Pharisee even after his conversion (Acts 23:6)? The goal of this post is to provide some context on who the Pharisees actually where, to help us better understand their role in the biblical story.

When the Jews began returning to their homeland after the Babylonian exile (2 Chron 36:23), they were not really getting their independence, and they were certainly not experiencing the kingdom of God. Cyrus was the messiah of Yahweh, a shepherd for Israel (Isa 44:28; Isa 45:1), but he was a Gentile; surely not the true messianic king. Israel had been rescued and redeemed from Babylon (Mic 4:10), and that was well and good, but Israel was far from subduing the surrounding nations who had been gathered against her (Mic 4:13). In fact, it wasn’t long after the return that the Persians themselves were superseded by the Greeks under Alexander, and Israel fell victim to the power struggles resulting from Alexander’s early death. You can read about this in 1 Maccabees chapter 1. The point most relevant here is that the Greeks and their culture came to so dominate the whole Mediterranean world that the Jews were faced with the question of conformity: Adopt Greek customs or not? Adopt only some? Which ones? Conform outwardly while maintaining inner separation? Prove your zeal for the Law by violent resistance and revolution? Retreat from society to live in a pure, isolated community?

In 164 B.C., the family of Judas Maccabee (Judas “the Hammer”) successfully revolted against the Greek ruler Antiochus, and for a while Israel had its independence. The family of Judas became the new ruling dynasty (called the Hasmonean dynasty after one of the family members), and it was not without its problems. There was often collusion with pagan powers, there was the blurring of distinction between priestly and kingly functions, there were assassinations and cruelties galore. If the return from exile hadn’t given way to the promised kingdom of God, the successful Maccabean revolt hadn’t done it either, despite being celebrated still today at Hanukkah and despite serving as a beacon of hope for many Jews in subsequent decades who still harbored dreams of throwing off the pagan yoke.

It was in that situation that the Pharisees arose. As noted above, the great and immediate questions of the day had to do with issues of conformity. How exactly was Israel to maintain its distinction as Yahweh’s covenant people? What stance could a faithful Jew take with regard to the ever-encroaching Gentile ways of life? It’s easy to imagine that in this climate, a party would take shape that saw itself as defending the old ways—the traditions of Israel—against both Gentile encroachment from outside and compromising corruption from inside. Such a group did arise, and that group was the Pharisees.

The Pharisees as a whole were not idiots. Greek (and very soon Roman) power was the reality, and it had to be responded to in some sort of realistic manner. As N.T. Wright suggests,

“[F]aced with social, political, and cultural ‘pollution’ at the level of national life as a whole, one natural reaction . . . was to concentrate on personal cleanness, to cleanse and purify an area over which one did have control as compensation for the impossibility of cleansing or purifying and area—the outward and visible political one—over which one had none. The intensifying of the biblical purity regulations within Pharisaism may well therefore invite the explanation that they are the individual analogue of the national fear of, and/or resistance to, contamination from, or oppression by, Gentiles.“

The Pharisaical focus on things like purity and Sabbath-keeping were thus driven, at least at the level of ideology, by a strong desire to maintain Israel’s distinction from the surrounding nations. It’s also important to realize that Pharisees had no official power. They weren’t even official teachers of the Law. They had no legal authority as Pharisees, although people in positions of power could have been Pharisees. They existed as a pressure group. An analogy which may be helpful is today’s Tea Party. The Tea Party is a “pressure group” which tries to do what it can in society to push for conservative politics—especially with regard to economics and foreign policy. The “Tea Party” as such has no legal authority, but they have succeeded in getting some of “their people” elected to office and they do exert considerable pressure on the Republican Party. Wright again:

“The Pharisees sought to bring moral pressure to bear upon those who had actual power; to influence the masses; and to maintain their own purity as best they could. Their aim, so far as we can tell, was never simply that of private piety for its own sake . . . Their goals were the honor of Israel’s god, the following of his covenant charter, and the pursuit of the full promised redemption of Israel.“

Thus Saul, for example, when he wanted to arrest Christians in Damascus, needed letters of authority from the high priest (Acts 9:1-2). In the early years of the Pharisees’ activity, the Hasmonean rulers were still interested in maintaining some appearance of ruling in accord with Israel’s Law. The Romans and Herods didn’t care so much about this, and so by the time of Jesus the Pharisees perhaps had less influence with the ruling elite, but could still hold themselves up as models for the common people. Their goals could take on different practical forms: Supporting armed resistance on the one hand, or withdrawing into Torah study and on the other (this second option is illustrated by Gamaliel in Acts 5:34, who recommended that the new Christian sect be left alone. Saul, already mentioned, would have been more in line with the first option of using physical violence).

It is certainly the case that the Pharisees’ insistence on maintaining the purity and separateness of the covenant people was driven by the belief that such a condition would find favor with God. What could be wrong with seeking to enforce—and with compelling others to enforce, either with violence or moral influence—Yahweh’s own Torah? But an official or theoretical ideology is a far cry from understanding and applying the Torah rightly, and it’s a far cry from the condition of the heart. Jesus rebuked the Pharisees for both of these things, for allowing the Tradition to usurp the injunctions of Scripture (Matt 15:5-6), and for the hypocrisy of their hearts (Matt 23:25).

Was Pharisaism wrong in principle? It doesn’t seem so. Yahweh had given his people the Law, and had called them to be separate from the nations. In the Gospels, the Pharisaical problem was that they were not following the Torah in truth, and were not following it in its true intent, which was to serve the Love of God and neighbor. They had allowed their practices to take over and usurp these overriding concerns. Many of them also were in fact lovers of money and privilege (Luke 16:14-15). Jesus rebukes them for this hypocrisy and for misunderstanding the Scriptures they claimed to believe and defend, and their wickedness was real and profound—it lead them to plot the murder of Christ (John 18:3).

Republished with permission.