Pilgrim’s Egress

or Three Ways to Live

“You are already full! You are already rich! You have reigned as kings without us — and indeed I could wish you did reign, that we also might reign with you! For I think that God has displayed us, the apostles, last, as men condemned to death; for we have been made a spectacle to the world, both to angels and to men. We are fools for Christ’s sake, but you are wise in Christ! We are weak, but you are strong! You are distinguished, but we are dishonored!” 1 Corinthians 4:8-10

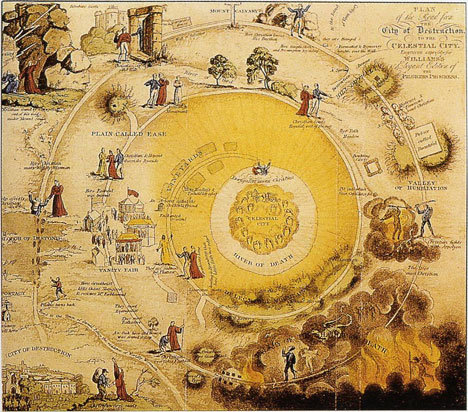

John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and its sequel speak some sharp truths and great comforts to the heart of a Christian, in bold images and colourful scenarios that are impossible to forget. But there’s something the famous author got terribly wrong. He omitted Hierarchy.

The storyline follows Christian as he leaves his family in the City of Destruction. Sometimes he is alone. Sometimes he has companions. Sometimes these are a godly help and sometimes they are satanic distractions, bad apples (and in the sequel, there are some quite literal bad apples.) But when do we ever see Christian in a position of authority or stewardship before his death?

As we progress through our lives with God, he puts us in greater and greater positions of responsibility. As we qualify, we become “public servants.” As Christ was obedient, the Father exalted Him. Jesus kept “giving this authority away” until He had none of it left — and then the Father gave Him all authority.

A comment on an earlier post reads:

“The Bible is not to be read to entertain us. Jesus was not sent to enlighten us but to save us. It is a detailed urgent message to you personally. God made the word flesh. Theologians wish to turn it back into the word. My favorite theologian? John Bunyan’s desperate Christian in Pilgrim Progress.”

Are we supposed to be desperate all the time? In one sense, yes. We feel spiritually dry because we are spiritually dry, or at least our DIY cisterns are. But the Garden of faithful service is kept green by a hidden spring. Jesus, and Elijah, had food that came from a secret source. While everyone else is suffering a famine under the Covenant curse (and being eaten by birds and beasts), God gives the faithful a miraculous perseverance: “unharmed” oil and wine. Constant desperation is the outcome of disobedience.

Now, we all have times of desperation. The saints do need each other. And the challenge is surely for Christian to persevere until the end. But at the end of the pilgrim’s progress he isn’t that much different. Sure, he has learned to trust God more through some crucial lessons. But he is taken out of the world before he is able to be much use to anyone else! It’s all about him.

I know, it’s an allegory, and it hammers home its point brilliantly, which is the reason for the novel’s cultural longevity. But the Narnia books of C. S. Lewis handle this matter of hierarchy a great deal better. Well, the books do. The movies recoil from it. The producers of the Narnia films do not have, or do not understand, Lewis’ worldview at all. Steven D. Boyer writes:

“Understanding [Lewis'] basic outlook does bring with it, however, one really substantial obstacle: we have to think carefully about a significant element in Lewis’s vision that does not play very well in our world, even among contemporary Christians. That element is Lewis’s peculiar fondness for hierarchy.

The word “hierarchy” does not have very pleasant connotations in our day, so to speak of someone being “fond of hierarchy” sounds very “peculiar” indeed. It is like admitting that your great-uncle Jack, really a fine old gentleman, never got over his childhood delight in pulling the wings off flies. Of course, this odd and even repulsive idiosyncrasy might be ignored by members of the family, out of their affection for Uncle Jack.

The only problem with treating Lewis this way is that his particular oddity reappears everywhere in his work, usually quite explicitly, and it has an exceptionally strong bearing upon the way he understands orthodox Christianity. If we are going to understand Lewis’s deeply Christian vision of the world, we will need to try hard to understand how this suspicious attraction to hierarchy is a part of it.

Lewis’s thinking begins with the Christian understanding of God as the Creator of the world, and of the world as God’s creation. The historic Christian doctrine of Creation requires Christians to insist on uniting two fundamental principles, and oddly enough, two principles that the contemporary outlook is often prone to separate.

First, it insists upon hierarchy. We might not use this term very often, but it is clear that any serious doctrine of creatio ex nihilo (“creation out of nothing”) involves the recognition of a very real hierarchical distinction between God and world. The difference between the great Creator who gives reality and the cosmos that receives reality is absolute. The one is utterly independent, the other utterly dependent. The one is worthy of all worship; the other rightly offers this worship. There is here a hierarchy of the deepest, richest kind, for in every imaginable respect, the world is subordinate—and rightly subordinate—to the God who creates and constantly sustains her.

Yet right alongside this affirmation of hierarchy in the Christian doctrine of Creation, we find the insistence that creation is fundamentally, unambiguously good—and with a goodness that grows directly out of its unqualified dependence upon its Creator. Note the surprising interpenetration of these two principles. Creation is not good in spite of its subordination to God, in spite of the hierarchy; it is good because of its subordination, because of the hierarchy. It is good because it is created, and to be created is to be glorious precisely by virtue of reflecting or showing forth the greater, higher glory of the Creator.

Indeed, as soon as any created thing ceases to be rightly subordinate to God, that creature ceases also to be good. It becomes a competitor with God, like Molech or Baal or Satan, rather than a servant of God. This is the essence of sin in Lewis’s mind: it is a turning away from our true creaturely status. It is an attempt to replace the goodness that naturally comes from being subordinate to God the Creator with a different, independent, autonomous goodness. It is a rejection of God.” [1]

Towards the end of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the four children are given, by grace, the four thrones the witch had been intent on keeping from them. By this stage, they rightfully deserve them, even Edmund. Unlike the Celestial City in Pilgrim’s Progress, these thrones are positions, not of safety and comfort, but of authority and responsibility. As qualified delegates of Aslan, they guarded the domain given to them for many years and were a great blessing to it.

That was the entire purpose of the Testing of Adam: qualifying him to rule, to sit on the throne God had prepared for Him as Covenant head.

As the grace of God changes us, and brings us to spiritual maturity, we are not simply sitting tight until Jesus comes to rescue us. We are to be soldiers and farmers and athletes thirsty for the success that only comes with sacrifice. [2]

That is the element that is missing from Bunyan’s stories. This world is something to be escaped, not brought into captivity to Christ. There is no hierarchy. There is Faithful’s companionship and martyrdom, but other than that it’s every man for himself. In the Narnia books, Lewis is intent on allowing Covenant hierarchy to shine at every opportunity.

Jesus’ disciples squabbled about who would sit on Jesus’ left and right. He didn’t tell them off for desiring thrones. He redefined rulership for them, by His own example. He told His disciples that they would indeed sit on twelve thrones and judge Israel. The more they humbled themselves, the more the Firstfruits church was exalted. The New Testament, and subsequent history, shows us that they had good success in all they did. [3] They ran the race for a crown, but in this race the last are first. Like Jesus, whatever sacrifices they made as “heads” brought a brilliant abundance in the Covenant body. [4]

Your responsibilities, however mundane they may seem, are thrones. If we are faithful in small things, God gives us bigger things. The first task of Solomon was to (very wisely) wipe out David’s enemies. The first task of the saints at the final resurrection will be to judge angels. Just imagine what daunting and glorious quests the King of Kings has for us after that!

“When you think ‘success,’ think Abel.” –Gary North, The Five Pillars of Biblical Success.

__________________________________________________

[1] Steven D. Boyer, Narnia Invaded.

[2] See The Go-Betweens.

[3] See Twelve Thrones.

[4] For a good read, see Why My Church Rebelled Against the American Dream.

January 4th, 2011 at 9:20 am

I should add that I am aware of Lewis’ ‘Pilgrim’s Regress.’ Its focus is quite different to Bunyan’s. The giants are not obvious sins but subtle philosophies, the “counterfeit Christianities” of the early 20th century. It does, like Bunyan’s stories, deal with the inward journey as an outward life. But I don’t ever remember ‘Regress’ being read and taught to children as a model for Christian living.

January 5th, 2011 at 1:54 am

I think you are quite right, Mike, even if you say things in a very post-mill way! But these two things — hierarchy and desperation — are not divisible. Christ ruled by submitting. We must reign while remaining desperate. I like your thought, and I think you point out an area where Bunyan — who otherwise BLEEDS Scripture — was more influenced by his culture. We share most of that culture, especially the material dualism (this world is bad, it would be better to be sitting on clouds, etc.)

January 5th, 2011 at 9:22 am

Yes Robert, I agree. I love Bunyan’s sermons, and this was probably beyond the scope of his allegory. It’s a good thing we have Narnia.

Are there people who are not postmillennial?