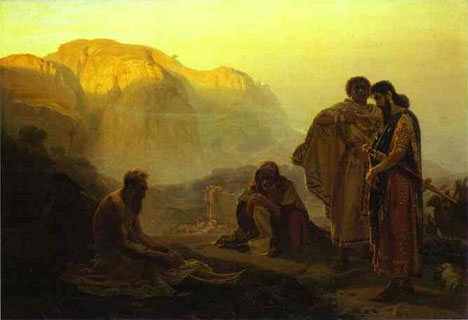

A Son for Glory

Here’s an [edited] excerpt from Toby Sumpter’s new book on Job, which I am really enjoying. It is a commentary with a pastoral heart, as evidenced below:

Here’s an [edited] excerpt from Toby Sumpter’s new book on Job, which I am really enjoying. It is a commentary with a pastoral heart, as evidenced below:

Continue reading

Here’s an [edited] excerpt from Toby Sumpter’s new book on Job, which I am really enjoying. It is a commentary with a pastoral heart, as evidenced below:

Here’s an [edited] excerpt from Toby Sumpter’s new book on Job, which I am really enjoying. It is a commentary with a pastoral heart, as evidenced below:

Continue reading

In Deep Comedy, Peter Leithart compares the Bible’s essentially comic and hopeful view of history with the Greco-Roman view, which is essentially and irredeemably tragic.

In Paul’s estimation, anyone who thought that the new life through Jesus pertained to some realm outside this history was simply an unbeliever. For the gospel says otherwise.

“Screw the truth into men’s minds.” – Richard Baxter

Doug Wilson, (in an interview a while back concerning Collision, I think), spoke about “copiousness.” It is the Christian’s practice of picking up striking thoughts and illustrations from reading, and from life, for future use. He advocates keeping a Commonplace book to jot things down.

“Keep a commonplace book. Write down any notable phrases that occur to you, or that you have come across. If it is one that you have found in another writer, and it is striking, then quote it, as the fellow said, or modify it to make it yours. If Chandler said that a guy had a cleft chin you could hide a marble in, that should come in useful sometime. If Wodehouse said somebody had an accent you could turn handsprings on, then he might have been talking about Jennifer Nettles of Sugarland. Tinker with stuff. Get your fingerprints on it.” [1]

He describes an incident that makes this book (or blog or mental practice) sound more like keeping caches of ammunition near at hand. Continue reading

James Jordan was asked whereabouts in the Bible is the best place to start reading it:

We should start in Genesis. What we should really do is pass a law that for five years you may only read Genesis through Joshua over and over again. So you get the foundation… When the Psalms and Ecclesiastes were written, they were written for people who were steeped in the earlier Scriptures. Ecclesiastes is not some mysterious book of philosophy. Ecclesiastes is all about the Feast of Tabernacles. The Feast of Tabernacles is literally the Feast of “Clouds.” That’s what sukkoth means. You get branches down out of a tree to make a little lean-to. Those branches up on that tree are a cloud. When you make a tree-house down here out of those branches, you’ve got your own little cloud. After a week it disintegrates. But God in His cloud, in His Tabernacle, goes on and on.

“I began writing this book some ten years ago, although my interest in Hebrew literary structure goes back a decade before that. My fascination with the subject was kindled when I began teaching Old Testament courses in seminary. At that time I was struck by the apparent lack of order within many of the biblical books. Jeremiah seemed hopelessly confused in its organisation; so did Isaiah and Hosea and most of the prophets. Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes appeared to be in almost complete disarray, and even the more orderly historical books, such as Joshua and Kings, showed signs of strangely careless organisation. Why did the biblical authors write like this? I would never write a book, an article, or even a private letter with such carelessness of arrangement.

I was intrigued by the possibility that the Hebrew authors might have organised their compositions according to literary conventions that were different from ours. I began to discover, over a period of years, that several structuring patterns rarely used by us were remarkably common in the books of the Hebrew Bible, particularly chiasmus (symmetry), parallelism, and sevenfold patterns. I was increasingly struck by how often these patterns had been utilised to arrange biblical books…

It was my mother who gave me a love for literature. She read to my brother Stephen and me regularly, from as early as I can remember. I still have many fond memories of those wondrous bedtime stories, whose structures — like the Bible — were designed for the ear, not the eye.”

David A. Dorsey, The Literary Structure of the Old Testament, p.9-10 (Preface).